Herd immunity may not work how we think

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments around the world scrambled to find the best strategy for containing the virus. Should they aim for elimination? Focus on protecting the vulnerable? Or, controversially, let the virus run its course to build herd immunity through natural infection? With limited data and high uncertainty, decisions were often made based on simplified models of how diseases spread through populations.

A new study from researchers at Aalto University suggests that our picture of herd immunity may be incomplete — and that understanding how people are connected could be just as important as knowing how many are immune.

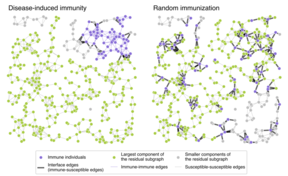

Herd immunity occurs when enough people in a population are immune to an infectious disease — either through vaccination or prior infection — so that its spread slows down or stops entirely. Through studying the way that social networks affect disease spread, the paper found that the way immunity is induced can drastically change how effective that indirect protection actually is.

‘Earlier models assumed immunity was scattered evenly, like cutting down every other tree throughout a forest to protect against wildfires,’ says Takayuki Hiraoka, lead author of the study. ‘But real outbreaks leave immunity clumped together — and that means the unaffected parts of the community remain dangerously exposed.’

As the “wildfire” of infection races through a forest, it spreads from one tree to another. To stop the fire, you can cut down every other tree before the flames reach them and create a gap that the flames cannot leap across. Gaps can also be created by the fire itself, as it burns down trees along its path. However, the fire tends to scorch only one corner of the forest, creating a clustered gap while leaving large stretches of forest untouched. Even if the same number of trees are cut or burned, the vulnerability of the forest to the next wildfire will be very different in these two scenarios.

Using network-based epidemic models and simulations, the team showed that this localization of immunity can make disease-induced protection far weaker than previously believed based on models that do not explicitly consider social networks. This effect is especially strong in spatially structured population models, which take into account people's tendency to interact with those nearby.

‘It may sound obvious that epidemic models should take into account the fact that you are more likely to interact with your neighbours than with people who live far away,’ Hiraoka explains. ‘But many modeling approaches ignore the effect of social networks and geographical space to keep things simple. We showed that this choice can have significant consequences for the model outcomes, both theoretically and using real-world data.’

The findings were recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers hope the findings will prompt deeper scientific discussions about the kinds of models used to guide public health policy. While no model can capture every detail of human behaviour, the findings underscore the importance of accounting for network effects when evaluating strategies –– and enacting policies –– to fight a pandemic.

‘Simplified models can be useful for intuition,’ says Professor Jari Saramäki, a co-author of the study. ‘But when it comes to decisions that affect millions of lives, we need to ask whether our assumptions match how people actually interact.’

This news article was originally published on the Aalto University Website on 11.7.2025

Read more news

A survey on users' experiences of Mykanta in collaboration between Aalto University and Kela

Senior university lecturer Sari Kujala's research group is exploring, in collaboration with Kela, users' experiences with the Mykanta online patient portal and the MyKanta mobile application.

Specialised AI models could be Finland's next global export

Finland has the potential to build AI solutions that are different from ChatGPT-like large language models. Aalto University's School of Electrical Engineering already has decades of experience in developing specialised, resource-efficient AI models. They could be a key component of future 6G networks, automation, and industrial systems – and the next competitive edge of our country.

Professor Patric Östergård becomes a member of the Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters

Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters is Finland's oldest science academy. It promotes scientific discussion, publishes scientific literature, awards prizes and provides financial support for research.